Witchcraft and Folk Magic

Here are the slides from our event at the Museum of Cambridge in October 2022. To learn more about these objects and their stories, listen to our special live episode.

Artwork depicting various witchy practices, 1592. Originally published in Peter Binsfeld’s Tractat von Bekanntnuss der Zauberer und Hexen (that’s The Confessions of Sorcerers and Witches to you and I). Binsfeld, a German bishop, was notorious as one of the most prominent witch-hunters of his time. He was instrumental in driving forward the Trier witch trials between 1581 and 1593; at least 368 people were executed during these trials. Binsfeld himself later died in Trier after contracting bubonic plague, a deservedly unpleasant end for him.

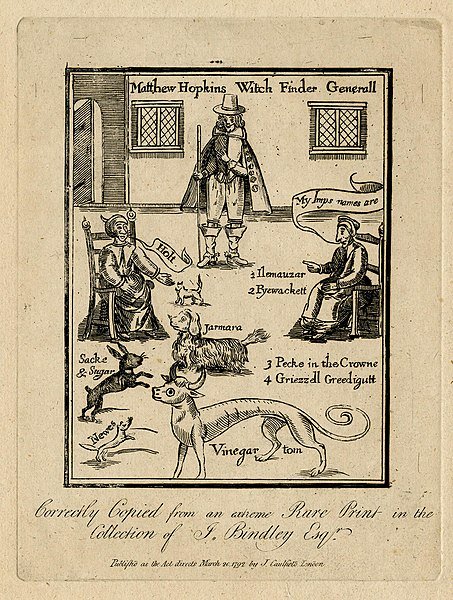

The rotter Matthew Hopkins, self-proclaimed Witchfinder General and scourge of East Anglia! What a fanciful hat and arrogant stance. Here depicted with those accused of witchcraft, alongside their intriguingly named familiars. Hopkins died at the age of 27, probably of tuberculosis. Good riddance to him too!

Illustration showing a witch and her familiars, taken from a published account of witch trials in Windsor in 1579.

The corp chreadh: a rudimentary clay body jabbed with pins, designed to bring pain and probably (judging by the number of pins) death to the intended victim. This little fellow can be seen on display in the Fen and Folklore room at the Museum of Cambridge, and was happily adopted as part of the Museum’s ‘Adopt an Object’ scheme as a result of our event.

Witch ball, also on display in the Fen and Folklore room. See the shiny surface, what witch could fail to be dazzled into submission by this?

A Bellarmine jug. These vessels, typically made in Northern continental Europe, were often used as counter magical devices against witchcraft. Perhaps the salt-glaze added a further layer of protection against any witch’s spirit trapped within. Witches hate salt!

Clear glass witch bottle, also on display in the F & F room at the Museum of Cambridge. Trouble with witches in your area? Fill one of these with an assortment of toenails, urine, hair, and iron nails for protection against curses and the evil eye.

A display from Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds which could be summed up with the phrase ‘things found in walls.’ Apotropaic magic (from the Greek for ‘to turn away evil’) was a popular form of folk magic that involved bricking up particular objects in the walls or under the floors of newly constructed buildings in the hope of warding off evil. Popular choices included mummified cats, horse bones, shoes, and bottles.